Warning messages have been used in a broad range of contexts for over half a century. Their utility is accepted in a broad range of settings related to safety and information sharing in contexts as diverse as medical containers and manufacturing, to road safety and building evaluation plans. While they have been deployed in relation to search engines since 2013, the evidence for their effectiveness was not measured or shared publicly, which motivated a series of randomised controlled experiments to establish their effectiveness.

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) is a research study designed to determine the effectiveness of an intervention or treatment. It’s considered a gold standard in many scientific fields, especially medicine, because it provides a rigorous method for establishing cause-and-effect relationships.

A series of three randomised control trials was run between 2018 and 2020, focusing on two key areas: viewing barely legal pornography (as a proxy for CSAM) and the non-consensual sharing of sexual images.

The experiments were conducted using a honeypot architecture, where the individuals being observed were unaware that the experiment was taking place. They were recruited via a social media advertising campaign for a male fitness website, enabling a target cohort of adult Australian males to be explicitly targeted. If they engaged with the advertisement and proceeded to the fitness website, they were then served further ads around real content that had been produced for the website. These ads were for real products, but also included advertisements for a pornography website that aligned with the given experiment. For more details on the honeypot architecture, please refer to this article.

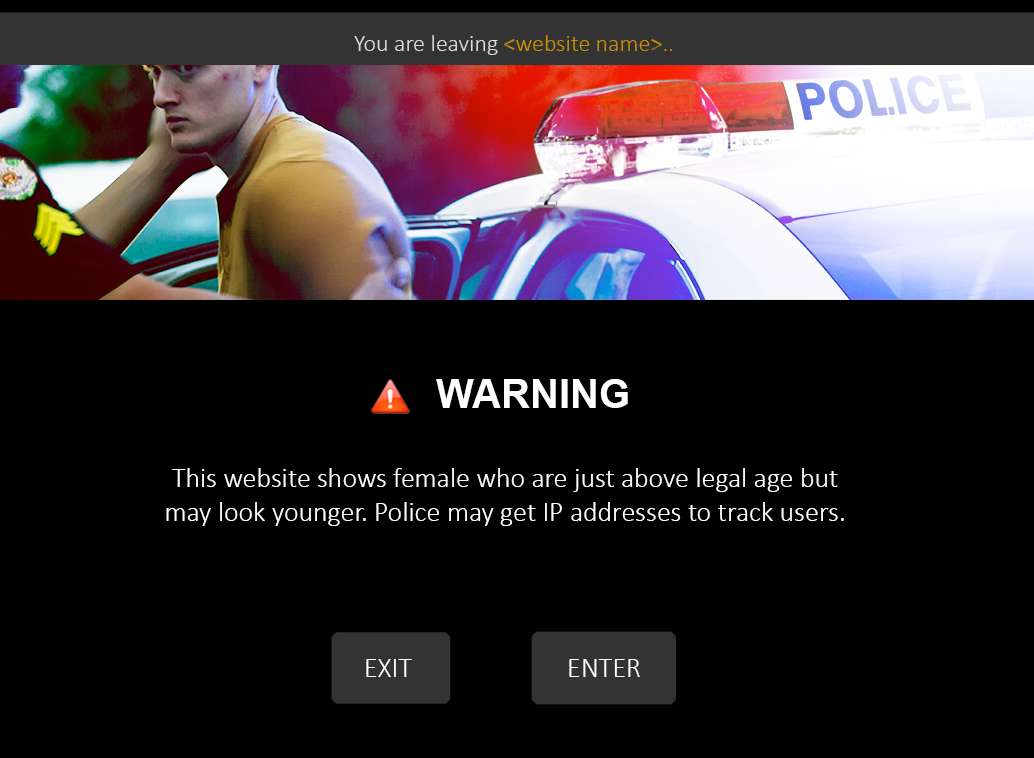

If they clicked on the advert, they were then entered into an experimental condition to trial a warning message, or the control group that then proceeded directly to the landing page of the fake pornography website. The warning message groups received a warning message for their experimental condition and were provided the option to continue to the website or to leave. Those that continued to the website, along with the control group, would see a landing page for the fake pornography website with an “enter” button, enabling the researchers to measure how many individuals proceeded to the website, and then how many then attempted to enter the website. The results of this choice were measured to assess the effectiveness of the warning messages.

Viewing Experiment 1: Law Enforcement vs Therapeutic Messaging

The first experiment examined the effectiveness of law enforcement messaging and therapeutic messaging. The honeypot received 31,162 visitors from the advertisements on social media, of which 555 individuals proceeded to click on the advert for a “Barely Legal” pornography website. This was used as a proxy for CSAM, as advertising a website as having CSAM would be illegal and also unlikely to be believable to respondents.

The study found that all the warning messages had a clear deterrent effect vs the control (no warning message). Images did not enhance warning effectiveness. The findings of this study suggest that online messages offering therapy to users interested in CSAM may be as effective as those with a law enforcement focus.

| Group 1 No message (N=100) 73% clicked |

Group 2 Policing text (N=81) 51% clicked |

Group 3 Policing image (N=117) 35% clicked |

Group 4 Referral text (N=120) 40% clicked |

Group 5 Referral image (N=137) 47% clicked |

The full paper, describing the method and the experiment’s outcomes, is available here.

Viewing Experiment 2: Law Enforcement vs Harm

The second experiment examined the effectiveness of messaging that considered the harm of the content in relation to both the victim and the viewer, as well as law enforcement themes related to the illegality of the material and the likelihood that it would be tracked by their IP address. The honeypot received 29,364 visitors from the advertisements on social media, of which 419 individuals proceeded to click on the advert for a “Barely Legal” pornography website – the same used in the first experiment.

The study found that deterrence-focused online warning messages significantly reduced the click-through to the barely legal pornography site. The result disproves the concern that CSAM-deterrent messages might be counterproductive because they could make CSAM seem more alluring to users. However, we also found that harm-focused messages had no significant impact on the click-through rate to the barely legal pornography site.

| Group 1 No message (N=100) 73% clicked |

Group 2 Harm to Viewer (N=74) 62% clicked |

Group 3 Harm to Victim (N=65) 55% clicked |

Group 4 Police may track your IP address (N=81) 51% clicked |

Group 5 Material may be illegal (N=99) 48% clicked |

The full paper, describing the method and the experiment’s outcomes, is available here.

Sharing Experiment: Law Enforcement vs Therapeutic Messaging

The third experiment examined the effectiveness of warning messages in relation to users sharing non-consensual sexual imagery. The honeypot received 28,902 visitors from the advertisements on social media, of which 528 individuals proceeded to click on the advert for a “Share My Girl”, a website that purported to provide access to pornography if they uploaded content.

This study has demonstrated that individuals can be dissuaded from sharing sexual images if they receive an online warning message concerning a potential breach of CSAM laws. The experiment trialled animation within the warning message, but no significant difference was found between the fidelity of the two warning message approaches.

| Group 1 No message (N=102) 60% clicked |

Group 2 Policing text (N=177) 43% clicked |

Group 3 Policing image (N=249) 38% clicked |

The full paper, describing the method and the experiment’s outcomes, is available here.

Conclusion

The RCTs established that warning messages could deter users from accessing material that was CSAM-adjacent or sharing non-consensual sexual imagery. The experiments were undertaken with a naïve population, providing an ecologically valid approach, while in a controlled experimental context with limited numbers.

These experiments were crucial in establishing that warning messages can be effective in deterring users from attempting to access CSAM online. However, the next step is to provide real world evidence of warning messages deployed at scale on platforms and services that users normally interact with. The reThink evaluation is the first example of such an evaluation, and hopefully more will follow as it is a key goal of the CSAM Deterrence Centre.